Roots of the LGBT struggle

recounts the development of the movement--from the battles of the 1960s through the fights taking place today.

WHEN THOUSANDS of people arrive in Washington to march for LGBT equality on October 11, they will come from many cities and many struggles, but with one central demand--full equality now.

Forty-six years ago, another civil rights march brought a similar demand to Washington. They came, as Martin Luther King Jr. said, to "cash a check."

"When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir," King said to the sea of people at the 1963 March on Washington. "This note was a promise that all men--yes, Black men as well as white men--would be guaranteed the 'unalienable rights' of 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.'

"It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note...Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked 'insufficient funds.'"

Like the marchers then, marchers today are here to tell the U.S. government that what we're owed is way past due.

LIKE THE civil rights movement of the 1960s, today's movement for LGBT equality didn't emerge overnight--nor is it anywhere near over yet. There has been years of organizing, with activists taking on difficult battles, fierce and bigoted opposition and discrimination, successes as well as setbacks, on the local level as well as the national--all of which informed the struggles to come.

Without the civil rights movement, there wouldn't have been the same kind of gay rights movement that erupted in the late 1960s and '70s. Some of the people who took part in the civil rights movement, as well as the anti-Vietnam War and women's movement, were closeted gays and lesbians who were learning lessons that would give them the courage to speak out and organize against this oppression.

Before the rush of activism in the late 1960s, courageous individuals organized where they could. But for the most part, their efforts were small and disconnected from one another.

As they faced fierce repression during the government's McCarthyite witch-hunt against the "enemy within," individuals in groups like the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society still tried to organize. But the climate of intense hysteria and fear had an effect on activists, who chose to be measured in their demands--to appear to conform and refrain from too defiant a stance.

The winds had shifted by the late 1960s, as liberation movements took up slogans like "Black Power." Activists were gaining confidence from those demanding liberation around them, and started imagining a place for their demands--in the streets.

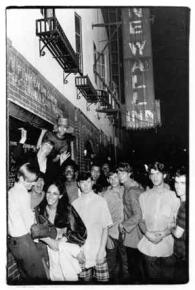

The Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 marked the beginning of a new gay rights movement. For six days and nights, gays, lesbians and transsexuals in New York City rioted and brought to the world's attention the terrible discrimination and bigotry faced by LGBT people. They also gave voice to a long-brewing anger that was waiting to explode--and now that it had, no one could put a cap on it.

The rebellion was sparked by a police raid--an everyday occurrence in gay bars--but the reaction it set off was not everyday, and offered a brand-new way of looking at the struggle for LGBT liberation.

Working-class and poor LGBT people of every race in New York City were confronting the police and challenging harassment head on. They spoke for people who were suffering similar situations in cities across the country. Suddenly, the daily humiliations and brutality were exposed for everyone to see--and they were being combated. The old ideas of moderation were thrown out the door.

As Sherry Wolf, author of Sexuality and Socialism, put it:

By the time the riots subsided, activists began distributing leaflets that read, "Do You Think Homosexuals Are Revolting? You Bet Your Sweet Ass We Are," and announced a meeting at a Village leftist venue known as Alternative U. What began as an ad hoc committee of Mattachine-New York to organize a march in commemoration of the riots evolved into a full-blown organization, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF).

In conscious tribute to the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front then fighting the U.S. government in Southeast Asia, these activists wanted to confront not just the stifling homophobia of U.S. society, but the entire oppressive and exploitative imperial edifice...almost all the newly radicalizing activists agreed that the old guard's approach needed to be upended.

Looking back years later on the debates between the more conservative Daughters of Bilitis and Mattachine leaderships, and the new radicals, one prominent militant, Jim Fouratt, summarized the tensions of that time: "We wanted to end the homophile movement. We wanted them to join us in making the gay revolution. We were a nightmare to them. They were committed to being nice, acceptable status quo Americans, and we were not; we had no interest at all in being acceptable."

ALL OF the social movements of the 1960s and early '70s began to go into retreat in the mid- to late 1970s, simultaneous with the end of the economic boom and the rise of high-profile anti-gay religious conservatives like Jerry Falwell.

In this context, many LGBT activists shifted more and more toward the Democratic Party for help. During the Reaganite 1980s, leaders of mainstream gay organizations--like their counterparts in the women's and African American organizations--turned their focus away from protests and toward getting a hearing in government, primarily by trying to get gay-friendly Democratic Party politicians in office.

LGBT people received little for their efforts. At a time when it was common knowledge that AIDS was ravaging the gay community and killing thousands, Democratic Party leaders distanced themselves from gay rights issues. The 1988 Democratic Party presidential nominee Michael Dukakis even voiced opposition to gay foster parents and a gay caucus in the party.

Bill Clinton raised expectations when he took office--he had promised an end to the discrimination of gays and lesbians in the military among other changes. Instead, he pushed through the "don't ask, don't tell" policy--a so-called "compromise" that only maintained discrimination in the armed forces.

On top of that, Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act--rather, the Denial of Marriage Act--into law, banning same-sex marriage.

With Barack Obama's victory last November, expectations were once again raised, as eight terrible years of George Bush doing the bidding of the religious right came to an end.

But while there was cheering in the streets over what signified a truly new era in American politics--the first African American elected president--there was also anger in the streets of California, when Proposition 8, the ban on same-sex marriages backed by religious conservatives, passed.

Though the mass protests in California and elsewhere seemed to come from nowhere, they were a cumulative response to all the rotten compromises and broken promises of the past. And the mobilizations involved not only LGBT people, but straight people as well--young and old, men and women, Black, white, Latino, Asian.

Despite what the Religious Right would have people believe, vast numbers of people today came of age knowing someone who is gay, lesbian or transgender--or are so themselves.

The activism that has taken place over the last year has shown people's desire to link their struggles together, fight back and win. When anti-gay attacks take place, activists rush to organize and oppose them. October's march can bring together these thousands of people organizing on many fronts in their cities and states--so that we can tell the government what we want.

The question of LGBT equality isn't if, but when. And as Rev. King said in 1963, now is the time.