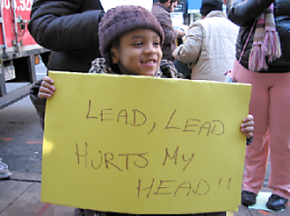

Using Black children as guinea pigs

reports on revelations of Black children purposefully exposed to lead paint that are drawing comparisons to the infamous Tuskegee Experiment.

ANOTHER HORRIFIC chapter in the history of American racism was revealed last month when a class action lawsuit was filed against the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore. The suit accuses the institute of intentionally exposing young Black children to lead paint and dust in order to study the effectiveness of various types of abatement strategies for decreasing lead levels in housing.

The suit alleges that beginning in 1993 and until 1999, Kennedy Krieger, which is affiliated with the prestigious Johns Hopkins University, moved Black families with children between the ages of 1 and 5 into apartments subsidized by the state, telling them that they were "lead safe."

However, the apartments allegedly contained lead dust and paint that put the children at great risk. Kennedy Krieger is accused of not informing parents of the risk of lead exposure and providing no medical care to children in the study.

Lead exposure is especially harmful to children; it can cause serious and permanent health problems, including learning disabilities and behavioral disorders.

These allegations have drawn comparisons to the infamous Tuskegee Experiment conducted by the United States Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972, in which hundreds of poor African American men were misled in order to study the affects of syphilis if left untreated.

Subjects in the study were not told they had syphilis; the government "deliberately denied treatment to the men with syphilis and they went to extreme lengths to ensure that they would not receive therapy from any other sources."

Many of the subjects died of syphilis, several passed it on to their wives, and many of their children were born with congenital syphilis, which can cause a host of serious health problems, including deformities, brain damage, seizures and death. The men were denied treatment for decades, even after penicillin was introduced as an effective treatment for syphilis in the 1940s.

SIMILARLY, KENNEDY Krieger allegedly did not inform the parents of the low-income African American subjects of their study that they risked exposing their children to unsafe levels of lead paint and dust. The lawsuit claims that over 100 children were placed at risk of exposure.

According to the New York Times, the lead plaintiff in the suit against Kennedy Krieger, David Armstrong, says he brought his 3-year-old son to the institute for treatment for elevated lead levels in his blood.

Armstrong agreed to participate in a two-year study, but was not told this would mean exposing his son to lead. He and his son, unaware of the health risks, continued to live in the contaminated apartment after the conclusion of the study. According to the Times:

Mr. Armstrong said blood was collected from his son for two years, but that no one told him the lead levels had increased. After the two-year mark passed, Mr. Armstrong said he continued to live in the two-bedroom apartment but did not hear from Kennedy Krieger.

During those two years, he said his son, now 20 years old, received no medical treatment for lead. Later, when Mr. Armstrong took his son to a pediatrician, the doctor detected blood lead levels two-and-a-half to three times higher than they had been before the family moved into the apartment.

Kennedy Krieger claims that the study "was conducted in the best interest of all of the children enrolled," citing the fact that "[with] no state or federal laws to regulate housing and protect the children of Baltimore, a practical way to clean up lead needed to be found so that homes, communities, and children could be safeguarded."

While that is certainly an argument for reforms to ensure lead-free housing for children in Baltimore and beyond, it does not justify the use of poor Black children as guinea pigs, subjecting them to the risk of permanent developmental disabilities and behavioral disorders, let alone without their parents' knowledge or informed consent.

The technology to test lead levels in paint had been available for decades prior to the study, and Kennedy Krieger was already aware of the crisis of lead poisoning among Black children in Baltimore because so many had been brought by their parents to the institute for care.

There were clear alternatives, such as the use of lead paint tests on animal subjects that did not involve violating the basic human right of Black children to a safe, lead-free home environment.

WHILE THE allegations contained in the lawsuit against Kennedy Krieger are outrageous enough and demand justice and accountability, the fact remains that poverty exposes poor children, especially Black children, to lead paint on a scale far greater than that of the study.

More generally, the disproportionately poor health of Black children is the shame of a nation, a crime whose victims are defenseless children targeted because they happened to be born Black in the United States. It is a preventable catastrophe on a mass scale in our society, the result of poverty and institutionalized racism that are behind racial disparities in access to health care, housing and healthy food.

According to the United States Census Bureau, nearly 40 percent of Black children, or 4.8 million, live below the poverty line. This compares with 22 percent of all children in the country, and 12.4 percent of white children.

These figures understate the actual scale of poverty in the country, as the poverty line is artificially low, based on a measure of the standard of living that dates back to the 1950s. In order to count as officially poor, a family of four must make less than $22,113 per year. For a single parent with two children, that number drops to $17,568. Especially in large cities with high costs of living, families making twice that amount can have difficulties making ends meet.

Poverty forces families into substandard housing, especially African Americans, for whom decades of racist de facto and legal housing discrimination ("redlining") have pushed them into old, dilapidated, unsafe apartments and houses.

The risk of lead exposure is highest in housing built before 1978, when the federal government outlawed the use of white lead paint in homes. Black children are disproportionately likely to live in old, untreated housing contaminated with lead and with chipping lead paint, the most common source of exposure. They therefore suffer a relatively larger share of the impact of lead poisoning.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, from 1991 to 1994, around the time the Kennedy Krieger study began, 11.2 percent of Black children ages 1 to 5 had elevated blood lead levels, nearly five times the rate of 2.3 percent for white children the same age. Although these rates decreased significantly by 1999-2001, racial disparities remained, with 3.1 percent of Black children ages 1 to 5 suffering from elevated blood lead levels, over twice the rate of 1.3 percent for white children.

Lead paint exposure is just one of many ways that poverty and institutional racism harm Black children's health.

According to the Children's Defense Fund, when compared with whites, Black children are less likely to have health insurance, their mothers are less likely to have access to prenatal care, they suffer from asthma at a 50 percent higher rate, they are more likely to be overweight or obese, they are less likely to have access to dental care, and more than 25 percent do not receive full immunizations against childhood diseases.

Health disparities fueled by poverty and racism are responsible for a situation where Black children are almost twice as likely as whites to be born with low birth-weight, which increases the risk of behavioral and learning problems. And "Black infants are more than twice as likely as White infants to die before their first birthday," according to the Children's Defense Fund.

To make things even worse, when Black children exhibit the behavioral problems associated with lead poisoning and other health disparities, rather than receiving the health care they need, they are more likely to be funneled into the criminal injustice system instead. Approximately one in three Black men born in the early 21st century will go to prison during their lifetime.

The Kennedy Krieger Institute's study is emblematic of the 1990s, a decade that saw the continuation of the attacks on the gains of the civil rights movement that were a central focus of the rise of the right wing in the 1980s. These included the "war on drugs," which precipitated the rise and growth of a system of racist mass incarceration that has locked millions of African Americans behind bars for nonviolent offenses, what author Michele Alexander has dubbed the "New Jim Crow."

Central to racism is the dehumanization of the oppressed. In the United States, the dehumanization of people of African descent began with their enslavement over 300 years ago and persists to this day. It is this context of racial oppression that makes possible atrocities like the Kennedy Krieger Institute study.