A working-class troubadour

pays tribute to Wobbly Joe Hill on the 100th anniversary of his execution.

My will is easy to decide

For there is nothing to divide.

My kin don't need to fuss and moan--

"Moss does not cling to a rolling stone"My body? Oh, if I could choose

I would to ashes it reduce

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers growPerhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again

This is my last and final will--

Good luck to all of you. Joe Hill.

-- Poem by Joe Hill, written the day before his execution

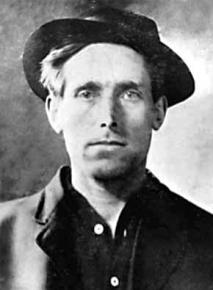

SHOUTING "FIRE, go on and fire!" Swedish immigrant worker Joel Hagglund--better known to the world as Joe Hill--was executed by a Utah state firing squad 100 years ago on November 19. Joe had become known in labor circles since joining the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies) while working on the docks in San Pedro, California, in 1910.

A typical Wobbly militant of the Western states, Joe tramped on boxcars, moving around for jobs and organizing fellow workers wherever he went. His fame came from his music. Accompanied by his guitar, Joe sang and wrote many of the songs in the IWW's Little Red Songbook. He thereby helped found the tradition of left-leaning working-class "folk music," as it was later called.

If Joe had a following before his arrest, he became internationally known once he was sentenced to death. The socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason published a death row letter from Joe, in which he said, "There had to be a 'goat,' and the undersigned being, as they thought, a friendless tramp, a Swede, and worst of all, an IWW, had no right to live anyway."

Tens of thousands of people signed petitions calling for clemency. Helen Keller appealed directly to President Woodrow Wilson to save Joe Hill, as did the Swedish ambassador. In response, Wilson asked Utah Gov. William Spry to look into the matter. But Spry refused.

At Hill's funeral in Chicago, 30,000 people marched, many in IWW red. In a farewell letter to IWW chief Bill Haywood, Hill famously wrote, "Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize." Ever since, Joe's memory and his memorials have provided occasion to do just that.

THOUGH SUPPRESSED and written out of history, powerful radical subcultures nestled within the emerging capitalist industrialism of the turn-of-the-century West. In addition to strikes, Joe Hill participated in the 1911 anarchist takeover of Tijuana, Baja California, and the 1912 free speech movement in San Diego.

When Joe moved to Utah in late 1913, the IWW and other unions like the Western Federation of Miners had organized there. Since 1910, there had been strikes among Bingham Canyon miners, Murray smelter workers and Tucker construction workers.

The Socialist Party had elected many members to local office in the state since 1901. Gov. Spry was elected on a promise to crack down on radical unionists, migrant workers and the left.

On the night of January 10, 1914, retired Salt Lake City cop John G. Morrison died at the hands of an unknown shooter. Morrison had said he was worried about revenge killers taking his life because of his role in sending them to prison. According to witnesses, the murderer called out, "Now I've got you," before shooting. Nothing was stolen from him.

On that same night, four other people were shot in Salt Lake in unrelated incidents. One of them was Hagglund, who went by the name Hillstrom (or Hill for short) to avoid anti-union blacklisting. He showed up at a doctor's office with a bullet wound through his abdomen, was treated and went home.

When the doctor later heard about Morrison's killing, he got suspicious and called the police. They arrested Hillstrom.

Unlike Wobbly martyrs Frank Little and Wesley Everest, the ruling class didn't target Joe for his revolutionary activities. But once they had him for other reasons, they opportunistically ignored the total lack of evidence or motive. Through the press, they incited the public and the jury to assume guilt on the basis of radicalism.

Joe had never met and had no connection to the victim. The shooting he himself suffered apparently had to do with an unrelated love triangle. Feeling no respect for the capitalist justice system, and possibly wishing to protect the woman he was involved with, Joe refused to answer certain questions about the events causing his injuries.

THE LEFT and working-class movements of the era knew how to campaign in solidarity with class struggle prisoners. Mass movements championed the Haymarket martyrs of 1887, Haywood and George Pettibone in 1905, and others. They became symbols of both capitalist (in)justice and revolutionary conviction.

Joe Hill, too, knew how to rise to the occasion. Continuing to write songs from jail, he refused to beg for mercy, refused to show fear, and used his position to urge struggle and confidence in ultimate victory.

After cremation, Joe's ashes were put in 600 envelopes and mailed to IWW locals across the country, which held services. Thus started the tradition of memorials to the martyred troubadour, held by Wobblies, unionists and leftists ever since.

Amazingly, some of Joe's ashes resurfaced in 1988. The U.S. Postal Service seized one of the envelopes for its "subversive potential" in 1917. Abbie Hoffman encouraged modern lefty singer songwriters Michelle Shocked and Billy Bragg to ritually eat some of the ashes.

But by then, the role of Joe's story in educating people about working-class history and struggle was established well beyond the need for ashes.

Celebrations of Joe's life typically involve singing. His irreverent, stark and inspiring songs, set to well-known tunes of his day, have become union and revolutionary classics. Joe's lyrics didn't so much mock religion as its use as a ruling-class tool:

If you fight hard for children and wife,

Try to get something good in this life,

You're a sinner and bad man, they tell,

When you die you will sure go to hell.You'll eat bye and bye,

In that glorious land in the sky,

Work and pray live on hay,

You'll get pie in the sky when you die.

Other songs taught hatred of scabs, damned the oppression of women, mocked racism and preached the good news of the future world where:

No one will for bread by crying,

We'll have freedom, love and health,

When the grand red flag is flying,

In the Workers' Commonwealth.

But the songs can't be appreciated much on the page. Joe wrote these songs for overworked or hungry workers in migrant camps or IWW halls. Singing them together, the workers would learn the ABCs of class struggle, sense their camaraderie, and strengthen their courage and faith in the cause.

To knit together the organizations that can give life to a new politics of struggle, we'll need to learn something from them about the use of art and music for the same purposes.