Radical Columbia

Colleges and universities try to maintain an image of being an oasis from the problems of the world--but social and political conflict are part of the fabric of the education system in a capitalist society, and so are the student protests that erupt when those conflicts come to the surface. New York City's Columbia University is no exception, as Columbia graduate shows in uncovering the hidden history of protest and struggle on one college campus.

ON THE surface today, few people would think that New York City's prestigious Columbia University is a site of political struggle. The luxurious plazas and colonnades of the Ivy League campus--possibly best known to most of America from the Ghostbusters movies--seem so far removed from the conflict-ridden world around it.

But in reality, Columbia has been rocked by fierce protest time and time again over the last century. Despite the university's liberal reputation, students have had to wage determined battles against a stubborn and repressive administration to win basic rights and freedoms.

The result has been a tempestuous history of resistance that shaped Columbia in important ways--and which the university today is careful to distort and conceal. Columbia's story is unique, of course, but there is a hidden history of struggle on most campuses around the U.S. Today, as a new generation confronts oppression and embraces socialism, this radical tradition demands our attention.

In particular, there are three decades in Columbia's history--the 1930s, 1960s, and 1980s--that offer brilliant examples of what mass struggle can accomplish.

Depression-Era Students Fight Back

The first student movement to fundamentally transform Columbia came during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Beginning at New York's municipal colleges and universities, communist and socialist students built a powerful, national movement to achieve democratic rights, support the burgeoning labor movement, and combat both American imperialism and European fascism.

Columbia's President Nicholas Murray Butler, who ran the university between 1902 and 1945, grew increasingly weary of the student movement.

Although he embraced a certain degree of radical discourse on his campus and employed several prominent left-wing professors, he did so only to maintain the university's image as a progressive institution. At heart, Butler was absolutely committed to global American dominance and the prevailing class order of society, both on and off campus.

By spring of 1932, Butler knew something was brewing. Student members of the Communist Party had established themselves on campus through their front organization, the Social Problems Club. In March, they led an delegation of 80 students to Harlan County, Kentucky.

Back in New York, the students hoped to raise awareness about the repression of coal miners who were striking for better pay and conditions. While in Kentucky, the students were detained and beaten, causing a liberal outcry back in New York and a dramatic change in consciousness among the Columbia student body.

The Columbia Daily Spectator, the campus newspaper, began publishing increasingly militant and critical material, which frightened the administration. This came to a head when the paper's editor Reed Harris penned an article indicting the administration for hyper-exploiting cafeteria workers in the John Jay dining hall. The University swiftly expelled Harris.

Students mobilized to defend Harris' right to free speech, likening President Butler to the repressive state officials in Kentucky and demanding that Harris be reinstated. On April 4, 2,000 students rallied on Columbia's central plaza, and two days later, the same number walked out of class.

The students were prepared to shut down the campus with an indefinite strike if Butler failed to reinstate Reed Harris. Finally, on April 20, Butler relented and allowed Harris to return to school. But the president remained determined to discipline the movement.

In 1933, Butler had the chance to confront the students once more. That year, after Hitler rose to power in Germany, the Social Problems Club set up an anti-fascist committee to demand a boycott of the Nazi dictatorship. They gained the support of a small group of faculty members, and lobbied the administration to sever all ties with German companies and institutions.

Instead of considering their proposals, Butler insisted on hosting Hans Luther, the Nazi Ambassador to the U.S., to speak at Columbia. In response, the students campaigned to force Butler to cancel the event. Butler appealed to the student body, arguing that Luther was a "representative of a friendly people and is entitled to be received...with courtesy and respect."

In the end, Luther was permitted to deliver his address at Columbia in November 1933. The anti-fascist students greeted him with a raucous protest of over 1,000 students rallying out in the freezing cold on Broadway Boulevard.

Police tried to move protesters to the other side of the street, and then proceeded to beat the students when they refused to budge. Several students were arrested, and three young women were dragged out of Horace Mann Auditorium for interrupting the ambassador's speech.

Several years later, Butler agreed to boycott Nazi Germany. But his furious repression of the student movement showed the lengths that the administration was willing to go to quell dissent.

Unfortunately, due both to the political failings of the movement and the broader forces, especially the Communist Party, connected to it, and to the ruthless state persecution of the left, the student movement collapsed over the following decade. Butler and his successors, Frank Fackenthal and future U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, were free to restore their unchecked authority over the campus.

The 1968 Rebellion

In the late 1950s, Columbia President Grayson Kirk sought to expand the university into Harlem and deepen its ties to the military. Columbia bought up dozens of buildings in the surrounding neighborhood and evicted thousands of mostly Black and Puerto Rican residents. At the same time, it signed contracts with the CIA and the secretive Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA).

Meanwhile, the winds of revolt had begun to stir again. During the 1960s, a new youth movement developed, embodied by organizations like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) active in the South during the civil rights movement.

The rebellious mood challenged not only Black oppression, but McCarthyism, authoritarianism and U.S. wars overseas. In Northern cities, segregated and impoverished Black neighborhoods began to revolt demanding greater rights and services.

At Columbia, a strong chapter of SDS fought to give students and faculty greater decision-making power and to oppose the Vietnam War. The Student Afro-American Society (SAS)--and the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters (BOSS), which mobilized women students at nearby Barnard College--advocated for Black empowerment. Anger swelled in Harlem against the Ivy league institution "on the hill" that encroached on the community and seemed to personify all of the contradictions of a segregated, racist society.

President Kirk and the Board of Trustees lit the fuse on this explosive situation when they decided to seize a large plot of Harlem's Morningside Park to construct a new gym for the University.

As Stefan Bradley describes in his book Harlem vs. Columbia University, Harlem residents rallied week after week against the planned gym during the summers of 1967 and 1968. Already well acquainted with Columbia's aggressive landlordism, Harlem residents called Kirk's proposal to build on their land "Gym Crow."

In 1968, the community's outrage fused with the student rebellion unfolding on campus. That April, during Columbia's memorial for Martin Luther King after he was assassinated, SDS leader Mark Rudd rushed the stage and screamed into the microphone: "How can these administrators praise a man who fought for human dignity when they have stolen land from the people of Harlem? If we really want to honor this man's memory, then we ought to stand together against this racist gym!"

The next day, students marched on the construction site and began to tear down the fences. The police responded by beating up the protesters.

The students decided to escalate their tactics to halt the construction of the gym. On April 22, members of SAS and BOSS occupied Hamilton Hall on Columbia's campus. After much debate, the SDS activists left Hamilton and took three other buildings--Fayerweather, Mathematics and Avery.

The Black students demanded an end to the gym project and greater Black representation on campus. SDS likewise insisted on calling off the gym, and added to the list of demands the termination of military contracts, a university statement in opposition to the Vietnam War, and new mechanisms to include students and faculty in school governance.

President Kirk called in the police. On April 30, at 2:30 a.m., a veritable army of 1,000 police officers descended on campus. "These kids need to be spanked," exclaimed one commander.

For the next five hours, the cops clubbed, dragged and kicked the occupying students into submission, arresting all 700 of them, and leaving blood in their wake. Asked about the beat-down, University Trustee Frode Jensen told reporters he thought the police "did a magnificent job."

The campus organized to hold the administration responsible for its crimes, once again using the strike weapon. Professors and students shut down the university for six weeks following the brutal police intervention, demanding that President Kirk resign, all charges against students be dropped and every point of the students' original demands be met.

With the university in a total crisis, the administration had little choice. Kirk canceled the gym project and met the strikers' demands across the board. Two months later, he resigned.

The occupation and ensuing strike was another dramatic example of how radical organizing could reshape campus life. Yet once again, student organizations nationwide lacked a political vision for their activity over the long term, and faced cutthroat repression by the state. Their organizations fell apart, and university administrations maneuvered to neutralize any sustained attack on their agenda.

At Columbia, it would take another decade after the struggle of 1968 to reboot the student movement on a mass scale.

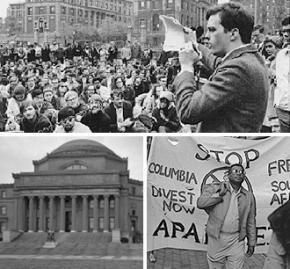

Resisting South African Apartheid

From the late 1970s until the early 1990s, the question of Black oppression and the apartheid regime in South Africa galvanized Columbia's campus.

In 1978, the campus-based Committee Against Investment in South Africa (CAISA) occupied Columbia's Business School to demand that the university divest its nearly $40 million dollars' worth of assets from the South African economy. The university condemned apartheid, but refused to go as far as divestment.

Between 1978 and 1983, CAISA and its successor, the Coalition for a Free South Africa (CFSA), hosted regular protests and teach-ins, including yearly "Apartheid Days" in the middle of the campus and boisterous rallies outside meetings of the Board of Trustees.

CFSA's persistent activism and the increasingly visible brutality of South Africa's oppressive system eventually won over the student body to the idea of divestment. In 1983, the student Senate passed a resolution in support of full divestment. A Daily Spectator poll indicated that 59 percent of undergraduate students favored the proposal.

But the administration refused to act. Board of Trustees Chair Samuel Higginbottom, also the president of Rolls Royce, belittled the senate's resolution as "foolish," "dramatic" and "futile."

CFSA lobbied again and again for the resolution, but got nowhere. Frustrated, they turned to a more militant approach. On April 4, 1985, the group blockaded the entrance to Hamilton Hall and erected a protest encampment that gathered some 300 to 400 people.

Outside Hamilton, now renamed "Nelson Mandela Hall," eight students announced that they would begin a hunger strike until President Michael Sovern agreed to meet with them and discuss divestment. The students won the support of 200 faculty members, who formed a group in support of their cause.

News of the occupation spread quickly. In South Africa, the families of two Columbia graduate students, Jose deSousa and Danisa Baloyi, were detained by the apartheid government as punishment for their children's protest.

Only after a full two weeks did the university president consent to meet with the hunger strikers, two of whom were, by that point, too weak to debate him. Sovern agreed to reconsider divestment. The protesters, fatigued but determined to continue agitating, ended the blockade on April 22.

The university tried to punish the movement. But stern hearings of the Rules Committee against activists only further enflamed the resistance. Danisa Baloyi charged the administration with showing more concern for disciplining the students than ending apartheid. As the trials dragged on, protesters blockaded the entrance to Rolls Royce headquarters in Midtown Manhattan to apply more pressure on Columbia's leading trustee, Samuel Higginbottom.

Finally, that August, President Sovern gave in and agreed to divest the university's endowment from South Africa. Although it took the university several years to complete the process, the student movement had won another tremendous battle against the administration.

Looking Ahead to Future Struggles

Over the following 30 years, Columbia students continued to mobilize for many different causes: to win an equitable admissions policy; to create a truly representative campus and curriculum; to end Columbia's land grabs and expansions; to fight against sexual violence; and to build resistance to both the First and Second Gulf Wars. More recently, the student group Columbia Prison Divest successfully pressured the administration into removing its endowment from private prisons.

These efforts, and the struggles of past generations, have made Columbia a far more diverse, democratic and humane institution than it would be without its legacy of student organizing.

Nonetheless, Columbia continues to perpetrate injustice. The university is still expanding into Harlem and displacing thousands of residents. Its newest $7 billion dollar expansion into West Harlem is intensifying rent hikes, police surveillance and incarceration in the surrounding communities.

On campus, students are agitating to win university divestment from fossil fuels and from Israel's apartheid regime over the Palestinian people. They are also fighting, among other things, for a living wage for student workers, university employees and adjunct faculty, for greater decision-making power for students, staff and faculty, and for long-overdue racial justice.

These ongoing battles point to the need for a renewal of mass protest on the scale of the historic student movements of the past. But they also show the need for organization, which can sustain the power of students, workers and community members to impact the university beyond a single moment or campaign.

At Columbia--and on virtually every campus in the U.S. for that matter--there is a treasure trove of hidden history waiting to be opened, with a whole host of lessons for future struggles. The task lies before today's radicals to excavate these histories and arm themselves for the fight ahead.