Resisting the backlash against women

The backlash against women has accelerated under Donald Trump, and the last few decades hold valuable lessons for activists today, writes .

THE ELECTION of Donald Trump sent shock waves across the country--especially for women.

Trump campaigned on defunding Planned Parenthood at the federal level as long as they perform abortions, and is now trying to make good on those promises. In April, Trump signed a law giving states the option to deny Title X funding to Planned Parenthood and other health care clinics that provide abortions.

Trump has emboldened Republican politicians to wage state-level legislative attacks on women's reproductive rights and has also given confidence to right-wing activists that target and harass women who use these clinics.

On May 13, a new offshoot of Operation Rescue called Operation Save America organized 100 anti-abortion activists to descend on a women's health clinic in Louisville, Kentucky. Ten members of the group were arrested after they locked arms and refused to move from the clinic's entrance in an attempt to shut down the last remaining abortion clinic in the state of Kentucky.

Not surprisingly, picketing outside abortion clinics rose sharply in 2016--three times the number of picketers the year before, according to the National Abortion Federation.

This summer in New York City, the state's attorney general filed a federal lawsuit against a number of these anti-abortion protesters who have been menacing patients outside Choices Women's Medical Center in Queens. They have pushed patients into the clinic wall, blocked car doors from being opened, shoved their heads and hands through patients' car windows, pushed volunteer escorts and threatened terrorist attacks on the clinic.

Protesters were caught yelling at patients walking in, "You can die at any moment" and "You don't know when you might get shot."

Trump's war on women is on all fronts--from promising to cut and privatize public services, which would destroy public-sector jobs, where women, and women of color, are disproportionately represented, to bragging about his own sexual assaults, to green-lighting Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to target immigrant women, including outside courts where they were filing orders of protection against their abusive husbands.

THE TRUMP administration represents an acceleration of the backlash against the gains of the women's movement of the late 1960s and early '70s that has been underway for decades, which takes aim at any attempts to win true equality for women, including reproductive rights, equal pay and an end to discrimination.

The backdrop to this backlash was the restructuring of the U.S. economy in response to an economic crisis of the 1970s, what today is commonly referred to as neoliberalism. Accomplishing this transformation required severely weakening trade unions, massive cuts to social services, privatization and deregulation alongside reversals of the civil rights, women's rights and environmental protections fought for and won by the massive social movements that defined the 1960s and early 1970s. The assault was immediate, swift and on every possible front.

The formation of the "New Right" was at the center of the backlash against women, with one central argument: women's equality was ruining the traditional family as an institution. The backlash required a powerful narrative that reinstated the so-called "sanctity of motherhood," a belief that women's primary identity and purpose in society is that of a mother: to breed, nurture and stand behind their man.

Evangelicals accused feminism of leading a "satanic attack on the home." Paul Weyrich, the so-called "Father of the New Right," described the threat of the women's movement this way:

There are people who want a different political order, who are not necessarily Marxists. Symbolized by the women's liberation movement, they believe that the future for their political power lies in the restructuring of the traditional family, and particularly the downgrading of the male or father role in the traditional family.

THE NEW Right found a political home in the Reagan administration and through conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation, which wrote manifestos that warned of the "increasing political leverage of feminist interests" and the "infiltration of a feminist network" into government agencies.

They called for a slew of countermeasures to minimize feminist power and policy, writing to the Reagan administration, "The fight against comparable worth (i.e. equality) must become a top priority for the administration." Their first bill drafted, called the Family Protection Act, had one goal: dismantling nearly every legal achievement of the women's movement.

In Susan Faludi's book about the 1980s, Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, she describes the Family Protection Act:

The act's proposals: eliminate federal laws supporting equal education, forbid "intermingling of the sexes in any sport or other school related activities"; require marriage and motherhood to be taught as the proper career for girls; deny federal funding to any school using textbooks portraying women in non-traditional roles, repeal all federal laws protecting battered wives from their husbands; and ban federally funded legal aid for any woman seeking abortion counseling or a divorce...

Other "family" legislative proposals from the New Right would follow in the next several years, and they were virtually all aimed as slapping down female independence wherever it showed its face: a complete ban on abortion, even if it meant the woman's death, censorship on all birth control information until marriage, a "chastity" bill; revocation of the Equal Pay Act and other equal employment laws; and, of course, the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment.

It's telling how powerful and threatening the women's liberation movement had become that it required a backlash that went to such an extreme. It was swift and devastating. Faludi continues:

Just when women's quest for equal rights seemed closest to achieving its objectives, the backlash struck it down... Just when support for feminism and the Equal Rights Amendment reached a record high in 1981, the amendment was defeated the following year. Just when women were starting to mobilize against battering and sexual assaults, the federal government stalled funding for battered women's programs, defeated bills to fund shelters and shut down its Office of Domestic Violence--only two years after opening it in 1979. Just when record numbers of younger women were supporting feminist goals in the mid-'80s, and a majority of all women were calling themselves feminists, the media declared the advent of a younger "postfeminist generation" that supposedly reviled (condemned) the women's movement. Just when women racked up their largest percentage ever supporting the right to abortion, the U.S. Supreme Court moved toward reconsidering it.

The backlash against working women, especially women of color, had the most devastating consequences because they had the most to gain from the women's and civil rights movement and the most to lose from the economic assault that was underway.

GIVEN HOW swiftly the backlash succeeded, it can be easy to draw the conclusion that men were inevitably on the side of turning the clock back on women's rights--that men felt threatened by women asserting their independence and rights and, therefore, agreed with the backlash in an attempt to regain their power.

Many feminists at the time held this position, but the reality was more complicated. Some working-class men were convinced of the ideas that the anti-feminist right were spreading, such as women returning to their more "traditional" roles, but not from a position of re-asserting any real power in society, but instead as a result of widespread feelings of powerlessness.

Plant closings during the 1980s put millions of working-class men out of the job, and only 60 percent found new jobs, about half of them at lower pay, according to Faludi. Feelings of powerlessness and economic insecurity led some men to feel threatened by women's assertion of independence and provided fertile ground for dangerous and reactionary ideas.

While all women suffered from the backlash, working-class women suffered the most: a re-segregation of the workforce took hold in the 1980s, leading women further into poverty and, therefore, once again, more dependent on men for their livelihood.

After 1983, women ceased making progress breaking into the blue-collar workforce, complaints to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission climbed and sexual harassment increased. The re-segregation of the workforce forced women almost entirely into the service and public sectors.

Those women who did break through into blue-collar work suffered heavily, as Faludi chronicles. At a construction site in New York, where few women found work, the men took a woman's work boots and hacked them into bits. Another woman was struck by a male co-worker over the head with a two-by-four. In a chemical plant in West Virginia, a woman arrived at work to find a sign stenciled onto a beam on the factory floor: "Shoot a Woman, Save a Job."

THE ATTACK on working women, fueled by an ideology that argued that women's place in society was primarily that of a mother and wife, also required a full-scale assault on women's bodies and their ability to control them.

There were more than 50 bills proposed to restrict Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision making abortion legal, within the first year of its existence. Three years after Roe, the Hyde Amendment was passed, targeting low-income women and immediately making abortion inaccessible, though it remained legal, by blocking Medicaid or any federal funds from covering the procedure.

The anti-abortion right that developed in this period made up some of the most violent and misogynist drivers of the backlash against women. Between 1977 and 1989, 77 family-planning clinics were torched or bombed, 117 were targets of arson, 250 received bomb threats, 231 were invaded and 224 vandalized.

Operation Rescue became the most successful vehicle for the anti-abortion crusade, mobilizing thousands to descend on cities and physically shut down clinics that provided abortion. Operation Rescue leader Randall Terry set out to not just end abortion, but also to ban all contraception and halt all pre-marital sex. In other words, he wanted to literally send women back into the Dark Ages.

Catholic bishops hired the country's largest public relations firm to launch a multimillion-dollar publicity drive against abortion, and the New York archdiocese proposed a new order of nuns, the Sisters of Life, that would be devoted exclusively to opposing abortion.

For the first time in U.S. history, legislators and state courts began to define the fetus as a legally independent "person" rather than an entity that is inseparable from the mother carrying it. In one egregious case, a woman whose cancer re-surfaced mid-pregnancy was forced to undergo life- threatening surgery, against her and her family's wishes, to save the fetus.

The surgery was sanctioned by a makeshift trial court held inside the hospital--complete with a lawyer for the fetus. The judge ruled against the woman and in favor of the fetus, and she was forced to undergo a surgery to extract a 26-week-old fetus. The fetus only survived two hours after a C-section was performed. The mother, as a result of the surgery, died the next day.

As fetuses' rights increased, women's rights diminished. This was especially true for Black women. Under the guise of the "war on drugs" and a declared epidemic of "crack babies," women's children were forcibly taken, pregnant women were drug-tested against their will, lawmakers advocated for the return of forced sterilization, and medical school professors recommended revoking public assistance for any mother caught under the influence of drugs.

Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer suggested rounding up all drug-using pregnant women and confining them to a "secure location" to halt the onset of a "bio-underclass."

What this history makes clear is that the backlash against women was used to justify economic policies of mass austerity, scapegoating mothers for the social ills actually produced by devastating cuts to social services legislated by wealthy men. And working-class men's acceptance of these supremely sexist ideas only made them less equipped to fight against the economic attacks that devastated their lives as well.

GIVEN THE success of the women's liberation movement, why wasn't there a successful resistance to the backlash?

The more radical wings of the women's movement, led by radical feminists, Black feminists and socialist feminists, made attempts to build militant, activist organizations that drew connections between sexism, racism and capitalism. They organized campaigns against forced sterilization and demanded that the reproductive rights movement include this demand.

They crashed Miss America pageants, founded the Coalition of Labor Union Women and created the Jane Collective, in which women activists trained themselves to perform abortions at a lower cost and higher safety levels than what was available to women under conditions of illegality. They led sit-ins at the Ladies' Home Journal, renaming it the Women's Liberated Journal.

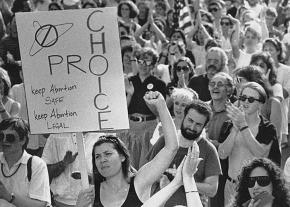

In 1970, the National Organization for Women (NOW) organized a "Women's Strike for Equality," with more than 50,000 women participating, calling for 24-hour child care centers, abortion on demand and equal opportunity in education and employment.

But a gulf widened between the more radical and Black feminist movements and those organizations led by white, middle-class women such as NOW. Despite the success of the Women's Strike for Equality and the broad support it received for its far-reaching Women's Bill of Rights, mainstream feminists rejected radical politics and instead embraced a strategy of pressuring the system from within--leading to a focus on influencing Democratic Party politicians through lobbying as a means to advance women's rights.

This strategy, which persists with a vengeance to this day, had devastating consequences for the women's movement and the more radical wings of the movement weren't strong enough, united enough or politically cohered enough to mount a successful alternative in the face of the backlash and the subsequent political retreat by feminists in the face of it.

Their exclusive focus on the needs of middle-class women meant efforts were focused almost exclusively on women seeking to enter the corporate and political elite, ignoring and alienating the lived reality of the vast majority of women. Other organizations such as Feminist Majority and NARAL (which in 1973 stood for "National Abortion Rights Action League" and was changed to "NARAL Pro-Choice America" in 2003), were formed and followed suit, compromising and conceding their way through the 1980s and 1990s, shifting the conversation away from unapologetic defense of abortion rights to one of "choice" and "privacy."

These organizations wanted their political messaging to be palatable to politicians and swing voters. In 1989, NARAL issued a talking points memo instructing staffers specifically not to use phrases such as "a woman's body is her own to control." Today, Planned Parenthood's defense of its own clinics in the face of a massive attack rarely mentions the word "abortion."

Activism for these mainstream women's organizations was reduced to campaigning for pro-choice Democrats, and that is their strategy to this day. Their loyalty to the Democratic Party meant that while the backlash continued through the 1990s under Democrat Bill Clinton--with attacks on abortion rights and welfare, and a ban on gay marriage--no national women's march or mobilization was organized in response.

This all paved the way for Trump to accelerate the backlash today. There is simply, at this moment, very little stopping them. There is however, as the massive Women's March after Trump's inauguration showed, massive numbers of women who are ready and willing to fight.

This is the contradiction we face: mass desire to resist but without resistance organizations. A key task for feminists today is to learn from this history and build the type of organizations that can pose a lasting challenge to the backlash and those who benefit from its acceleration.