Why we remember 1917

The promise of the Russian Revolution--its example of mass democracy in action, reaching into every corner of society--shows its relevance for us 100 years later.

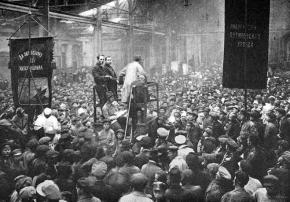

ONE HUNDRED years ago today, the world was turned upside down when a workers' government came to power in Russia.

Eight months earlier, Russia's ruler, the Tsar, had been overthrown in an eruption of strikes and street protests that took only five days to bring down a cruel and seemingly all-powerful tyrant. That alone would have qualified 1917 Russia for the history books.

But the mass mobilizations that ended the Tsar's reign weren't finished. The Provisional Government that came to power in early 1917 failed to satisfy the urgent demands of the masses of workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors that propelled them to revolt--most importantly, to end the carnage of the First World War.

On November 7--October 25 according to the old Julian calendar in use in Russia at the time--those masses did something that had never happened before and hasn't since in sustained form: They overturned a government committed to defending the system of private property and war in favor of a revolutionary "commune-type state," as Lenin called it, standing for peace for the soldiers and sailors, land for the peasants and bread for the working class.

Even 100 years later, this example remains a threat. The Russian Revolution suffered, from the beginning, an unending campaign of slander to try to discredit it--not to mention a physical campaign of civil war and invasion that was ultimately, if not immediately, successful in strangling the workers' state.

But for all that, it has been impossible to erase 1917. Many millions of people have been inspired by its most essential feature--that it was an incredible exercise in mass democracy. All the honest witnesses to the revolution, even its critics, acknowledged this about Russia in 1917.

Democracy took on a new and unique form that allowed elected representatives, chosen freely in factories, trenches and farms throughout Russia, to make decisions collectively. These representatives or delegates came together in workplace or local, then regional, then national councils--or "soviets," which is merely the word for council in Russian.

The soviets first emerged not at the urging of a party manifesto, but as a product of struggle during a failed revolution in Russia a dozen years before. They re-emerged immediately after the Tsar fell, just as similar formations have appeared in revolutionary upheavals in other countries and circumstances.

The fall of the Provisional Government and the establishment of the soviets as the governing power in Russia has gone down in history as the October Revolution, because of when it took place, according to the old Julian calendar, or the Bolshevik Revolution, because of the leading role played by that party of revolutionary socialists.

Though these names tell part of the story, it is more precise to remember November 7 as the Soviet Revolution--the triumph of the greatest expression of grassroots revolutionary democracy the world has yet seen.

ONE OF the ways that revolutions are misremembered is their stories are narrowed to the final act. The February Revolution in Russia comes down to the street battles during those five days that brought down the Tsar, and the October Revolution is limited to the insurrection that overwhelmed the forces of the old order and established the soviets as the undisputed power in Russia.

But these are just the climactic moments of a revolution--the endpoint of a longer period of struggle, in which the rulers face a growing crisis at the same time as mass of working people become more confident of their own power.

At the beginning of the process, the goals for change can be modest, limited to a few reforms in the way the system operates--and progress appears as tiny steps, when it appears at all.

But beneath the surface, people whose names won't be remembered in history books become involved and radicalized--and the struggle itself gives them a better sense of all there is to fight for. The act of toppling a tyrant and taking over political power is the final step of a revolution that has already been felt in workplaces, among communities, in cities, towns and villages, throughout society.

Even seemingly spontaneous revolts like the February uprising are prepared for over months and years--by both the countless grievances and conflicts coming to the surface and becoming an issue to struggle over, and by the times between struggles when, crucially, some people take up the task of understanding the fights of the past and analyzing the present to be ready for the future.

The Russian Revolution would not have been possible without the hundreds of thousands of revolutionaries concentrated in the Bolshevik Party, along with those on the left wings of the Menshevik, Socialist Revolutionary and anarchist parties.

The Bolsheviks didn't call for an uprising to overthrow the Tsar in February, but when it began, sparked off by strikes by women textile workers on International Women's Day, they were prepared by years of study and struggle to put forward tactics, strategies and a political analysis that looked to the power of mass workers' action and democracy.

The Bolsheviks did support the call for the October insurrection to bring down the Provisional Government, but only after their party and its allies had won countless arguments and persuaded masses of people to revolutionary views. Lenin and the Bolsheviks judged that they had won leadership concretely--when their party had gone from being a small minority in the soviets in early 1917 to the clear majority by October.

American journalist Albert Rhys Williams, who was an eyewitness to the revolution, captured the relationship perfectly when he wrote: "The revolutionists did not make the revolution. They made the revolution a success."

In this remark lies a profound lesson about both the limits of what radical organizers are able to accomplish by themselves, while they and their ideas are still a minority--and a confirmation of why it matters that individuals chose to dedicate their lives to working-class revolution before this goal seems remotely realistic to most people.

IF ANY further evidence of the importance of the Russian Revolution is needed, consider its accomplishments--not just over the few years that it survived before succumbing to a counterrevolution led by Joseph Stalin, but just in the first days after October.

The national congress of soviets, acting as the highest governing body in Russia, dispatched delegates to negotiate the terms of ending Russia's part in the First World War. It repudiated the Tsarist regime's alliances with other imperial powers and its claims on oppressed nations.

The workers' state adopted a breathtaking land reform program, nationalized the banks and voted to coordinate workers' control through elected factory committees. The old police forces were abolished, allowing popular democracy to flourish.

Years and decades before they could in the West, women got the right to vote, obtain legal abortions, divorce their husbands and access childcare. Laws outlawing homosexuality were struck down.

Not only that, but the workers' state supported initiatives for everything from organizing communal kitchens to systematic education in a mostly illiterate society. This was necessary to make the advances for liberation and freedom decreed by the soviets a reality felt in all people's lives.

This is what becomes possible when the working class has power--not just the power to protest and resist, but the power to remake the world as the collective rulers of society.

We badly need that power today if we want to save the planet; to use the vast resources of the modern economy to guarantee free education, health care and more; to obliterate racism, sexism and all forms of oppression; to make reparations for centuries of imperialist wars and occupations.

We know from history that workers and oppressed peoples can win reforms that make conditions and circumstances better in the here and now. These struggles are critical to the everyday activities of socialists, because we support every expansion of democracy and victory for justice on its own terms, but also because these struggles prepare working people to fight for more.

But we also know from history that reforms are precarious. No matter how immense the struggle, if the power of the ruling class remains intact, than their side has retained the power to accumulate greater wealth and control, including by taking back previous reforms--and our side doesn't have the power we need to remake the world.

That's another reason to remember 1917--as the best glimpse yet of how a different kind of society might be organized.

BUT ISN'T revolution a pipe dream? A historical curiosity, unimaginable in the modern world? We're certainly told that often enough, and not only by the ruling class and the institutions they control.

Certainly we are not living in revolutionary times today--nor have the kind of mass struggles that even put revolution on the agenda been common in recent history. The conditions of mass murder by world war and economic destitution that drove the Russian Revolution aren't the conditions we face today.

Yet with the heightened imperialist tensions, particularly in Asia, we are closer to world war than the media would have us believe. The arrogance and greed of the ruling class remains intact--to the extent that the out-of-touch twittering of the "most powerful man in the world" shares the same vacant, inhuman spirit as the diary entries of the Tsar famously quoted by Leon Trotsky in his History of the Russian Revolution.

The ruling class of 2017 is every bit as capable of committing atrocities today--and with a century's worth of technological and intellectual developments, these crimes are more deadly and dangerous, to the extent that the future of the planet is at stake now.

In the face of such a world, working people and social movements today often don't seem to possess the confidence to even go on strike or protest, much less take over the factories and offices, and rise up against the ruling class.

But don't forget: Confidence is learned in struggle, starting with seemingly modest struggles that don't aim to change the world, but end up contributing to a greater transformation. And when the learning process gets going, it can go very, very fast.

That's one of the most enduring lessons of 1917--how that revolutionary year touched and changed masses of people who never would have imagined themselves capable of what they accomplished.

In the History of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky quotes a former Tsarist general whose words sum up the ruling class's enduring hatred of this aspect of the revolution:

Who would believe that the janitor or watchman of the court building would suddenly become Chief Justice of the Court of Appeals? Or the hospital orderly manager of the hospital; the barber a big functionary; yesterday's ensign the commander-in-chief; yesterday's lackey or common laborer the town master; yesterday's train oiler chief of division or station superintendent; yesterday's locksmith head of the factory?

Who indeed? This was the promise of the Russian Revolution and the tragedy that it didn't--and, in fact, could not--survive to be an example in real life today.

So that promise is still to be realized--and one small step toward that for a new generation of socialists to uncover and understand the history of the Russian Revolution, so its lessons can be put to use in achieving a future socialist society.