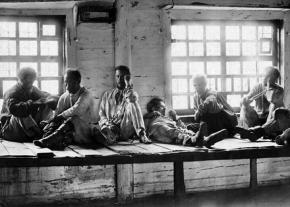

The red convicts of Cherm

SocialistWorker.org is continuing its series 1917: The View from the Streets with excerpts from a firsthand account of the revolution by socialist journalist , written for the New York Evening Post and published as a book in 1921. Along with the more famous Ten Days That Shook the World by fellow journalist John Reed, Williams' Through the Russian Revolution provides a riveting picture of the struggle.

In the excerpt below from chapter fourteen, Williams chronicles a stop during a journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway after the October Revolution and the establishment of a workers' government. Most of Williams' fellow passengers are opponents of the revolution--"landowners, speculators, war-profiteers, ex-officers in mufti, evicted officials, and three overpainted ladies"--with a very different attitude toward the penal colony of Cherm. SW's series on 1917 is edited by John Riddell and co-published at his website.

THE ÉMIGRÉS on our train had many points of conflict. But on one point they agreed: the grave danger lying ahead of us in Cherm, the great penal colony of Siberia.

"Fifteen thousand convicts in Cherm," they said.

"Criminals of the worst stripe----thugs, thieves and murderers. The only way to deal with them is to put them in the mines and keep them there at the point of the gun. Even so, it is too much liberty for them. Every week there are scores of thefts and stabbings. Now most of these devils have been turned loose, and they have turned Bolshevik. It always was a hell-hole. What it is now God only knows."

It was a raw bleak morning on the first of May, when we rode into Cherm (Chermkhovo). A curtain of dust, blown up by a wind from the north, hung over the place. Curled up in our compartment half asleep, we woke to the cry, "They're coming! They're coming!" We peered thru the window. Far as we could see nothing was coming but a whirling cloud of dust. Then thru the dust we made out a glint of red, the gray of glittering steel, and vague, black masses moving forward.

Behind drawn curtains, the émigrés went frantically hiding jewels and money, or sat paralyzed with terror. Outside, the cinders crunched under the tread of the hob-nailed boots. In what mood "they" were coming, with what lust in their blood, what weapons in their hands, no one knew. We knew only that these were the dread convicts of Cherm, "murderers, thugs and thieves"---and they were heading for the parlor-cars.

Slowly they lurched along, the wind filling their eyes with dust and soot, and wrestling with a huge blood-red banner they carried. Then came a lull in the wind, dropping the dust screen and bringing to view a motley crew.

Their clothes were black from the mines and tied up with strings, their faces grim and grimy. Some were ox-like hulks of men. Some were gnarled and knotted, warped by a thousand gales. Here were the cannibal-convicts of Tolstoy, slant-browed and brutal-jawed. Here was Dostoyevsky's "House of the Dead." With limping steps, cheeks slashed and eyes gouged out they came, marked by bullet, knife and mine disaster, some cursed by an evil birth. But few, if any, were weaklings.

By a long, grueling process the weak had been killed off. These thousands were the survivors of tens of thousands, driven out on the gray highroad to Cherm. Thru sleet and snow, winter blast and summer blaze they had staggered along. Torture-chambers had racked their limbs. Gendarmes' sabers had cracked their skulls. Iron fetters had cut their flesh. Cossacks' whips had gashed their backs, and Cossacks' hoofs had pounded them to earth.

Like their bodies their souls, too, had been knouted. Like a blood-hound the law had hung on their trail, driving them into dungeons, driving them to this dismal outpost of Siberia, driving them off the face of the earth into its caverns, to strain like beasts, digging the coal in the dark, and handing it up to those who live in the light.

Now out of the mines they come marching up into the light. Guns in hand, flying red flags of revolt, they are loose in the highways, moving forward like a great herd, the incarnation of brute strength. In their path lie the warm, luxurious parlor-cars---another universe, a million miles removed. Now it is just a few inches away, within their grasp. Three minutes, and they could leave this train sacked from end to end as tho gutted by a cyclone. How sweet for once to glut themselves! And how easy! One swift lunge forward. One furious onset.

But their actions show neither haste nor frenzy. Stretching their banners on the ground they range themselves in a crescent, massed in the center, facing the train. Now we can scan those faces. Sullen, defiant, lined deep with hate, brutalized by toil. On all of them the ravages of vice and terror. In all of them an infinitude of pain and torment, the poignant sorrow of the world.

But in their eyes is a strange light---a look of exaltation. Or is it the glitter of revenge? A blow for a blow. The law has given them a thousand blows. Is it their turn now? Will they avenge the long years of bitterness?

The Comrade Convicts

A hand touches our shoulder. We turn to look into the faces of two burly miners. They tell us that they are the Commissars of Cherm. At the same time they signal the banner-bearers, and the red standards rise up before our eyes. On one in large letters is the old familiar slogan: Proletarians, arise! You have nothing to lose but your chains. On another: We stretch out our hands to the miners in all lands. Greetings to our comrades throughout the world.

"Hats off!" shouts the commissar. Awkwardly they bare their heads and stand, caps in hand. Then slowly begins the hymn of the International:

Arise, ye prisoners of starvation!

Arise, ye wretched of the earth!

For justice thunders condemnation,

A better world's in birth.

No more tradition's chains shall bind you;

Arise, ye slaves! No more in thrall.

The world shall rise on new foundations.

You have been naught: you shall be all."

I have heard the streets of cities around the world, ringing to the "International," rising from massed columns of the marchers. I have heard rebel students send it floating thru college halls. I have heard the "International" on the voices of 2,000 Soviet delegates, blending with four military bands, go rolling thru the pillars of the Tauride Palace. But none of these singers looked the "wretched of the earth." They were the sympathizers or representatives of the wretched. These miner-convicts of Cherm were the wretched themselves, most wretched of all. Wretched in garments and looks, and even in voice.

With broken voices, and out of tune they sang, but in their singing one felt the pain and protest of the broken of all ages: the sigh of the captive, the moan of the galley-slave lashed to the oar, the groan of the serf stretched on the wheel, the cries from the cross, the stake and the gibbet, the anguish of myriads of the condemned, welling up out of the long reaches of the past.

These convicts were in apostolic succession to the suffering of the centuries. They were the excommunicate of society, mangled, crushed by its heavy hand, and hurled down into the darkness of this pit.

Now out of the pit rises this victory-hymn of the vanquished. Long bludgeoned into silence, they break into song--a song not of complaint, but of conquest. No longer are they social outcasts, but citizens. More than that--Makers of a New Society!

Their limbs are numb with cold. But their hearts are on fire. Harsh and rugged faces are touched with a sunrise glow. Dull eyes grow bright. Defiant ones grow soft. In them lies the transfiguring vision of the toilers of all nations bound together in one big fraternity--The International.

"Long live the International! Long live the American workers!" they shout. Then opening their ranks, they thrust forward one of their number. He is of giant stature, a veritable Jean Valjean of a man, with a Jean Valjean of a heart.

"In the name of the miners of Cherm," he says, "we greet the comrades on this train! In the old days how different it was! Day after day, trains rolled thru here, but we dared not come near them. Some of us did wrong, we know. But many of us were brutally wronged. Had there been justice, some of us would be on this train and some on this train would be in the mines.

"But most of the passengers didn't know there were any mines. In their warm beds, they didn't know that way down below were thousands of moles, digging coal to put heat in the cars and steam in the engine. They didn't know that hundreds of us were starved to death, flogged to death or killed by falling rock. If they did know, they didn't care. To them we were dregs and outcasts. To them we were nothing at all.

"Now we are everything! We have joined the International. We fall in today with the armies of labor in all lands. We are in the vanguard of them all. We, who were slaves, have been made freest of all.

"Not our freedom alone we want, comrades, but freedom for the workers thruout the world. Unless they, too, are free, we cannot keep the freedom we have to own the mines and run them ourselves.

"Already the greedy hands of the Imperialists of the world are reaching out across the seas. Only the hands of the workers of the world can tear those clutches from our throats."

The range and insight of the man's mind was amazing. So amazed was Kuntz that his own speech in reply faltered. My hold on Russian quite collapsed. Our part in this affair, we felt, was wan and pallid. But these miners did not feel so. They came into the breach with a cheer for the International, and another for the International Orchestra.

The "Orchestra" comprised four violins played by four prisoners of war; a Czech, a Hungarian, a German and an Austrian. Captured on the eastern front, from camp to camp they had been relayed along to these convict-mines in Siberia. Thousands of miles from home! Still farther in race and breeding from these Russian masses drawn from the soil. But caste and creed and race had fallen before the Revolution. To their convict miner comrades here in this dark hole they played, as in happier days they might have played at a music festival under the garden lights of Berlin or Budapest. The flaming passion in their veins crept into the strings of their violins and out into the heart-strings of their hearers.

The whole conclave---miners, musicians and visitors, Teutons, Slavs and Americans---became one. All barriers were down as the commissars came pressing up to greet us. One huge hulking fellow, with fists like pile-drivers, took our hands into his. Twice he tried to speak and twice he choked. Unable to put his sentiments of brotherhood into words he put it into a sudden terrific grip of his hands. I can feel that grip yet.

For the honor of Cherm he was anxious that its first public function should be conducted in proper fashion. Out of the past must have flashed the memory of some occasion where the program of the day included gifts as well as speeches. Disappearing for a time, he came running back with two sticks of dynamite---the gifts of Cherm to the two Americans. We demurred. He insisted. We pointed out that a chance collision and delegates might disappear together with dynamite---a total loss to the Internationale. The crowd laughed. Like a giant child he was hurt and puzzled. Then he laughed, too.

The second violinist, a blue-eyed lad from Vienna, was always laughing. Exile had not quenched his love of fun. In honor of the American visitors he insisted upon a Jazze-Americane. So he called it, but never before or since have I heard so weird a melody. He played with legs and arms as well as bow, dancing round, up and down to the great delight of the crowd.

Our love-feast at last was broken in upon by the clanging signal-bell. One more round of handclasps and we climbed aboard the train as the orchestra caught up the refrain:

It is the final conflict,

Let each stand in his place;

The Internationale--

Shall be the human race.

There was no grace or outward splendor in this meeting. It was ugliness unrelieved--except for one thing: the presence of a tremendous vitality. It was a revelation of the drive of the Revolution. Even into this sub-cellar of civilization it had penetrated into these regions of the damned it had come like a trumpet-blast, bringing down the walls of their charnel-house. Out of it they had rushed, not with bloodshot eyes, slavering mouths and daggers drawn, but crying for truth and justice, with songs of solidarity upon their lips, and on their banners the watchwords of a new world.

The Émigrés Unmoved

All this was lost upon the émigrés. Not one ray of wonder did they let penetrate the armor of their class-interest. Their former fears gave way to sneers:

"There is Bolshevism for you! It makes statesmen out of jail-birds. Great sight, isn't it? Convicts, parading the streets instead of digging in the mines. That's what we get out of Revolution."

We pointed to other things that came out of Revolution---order, restraint and good-will. But the émigrés could not see. They would not see.

"That is for the moment," they laughed. "When the excitement is over they'll go back to stealing, drinking and killing." To these émigrés it was at best a passing ecstasy that would disappear with our disappearing train.

Leaning out from the car steps we waved farewell to the hundreds of huge grimy hands waving farewell to us. Our eyes long clung to the scene. In the last glimpse we saw the men of Cherm with heads still bared to the cutting wind, the rhythmic rise and fall of the arms of "Jean Valjean," the red banner with "Greetings to our Comrades thruout the World," and a score of hands still stretched out towards the train. Then the scene faded away in the dust and distance.

Two years later Jo Redding came back to Detroit after working in Cherm and watching the Revolution working there. He reports its permanent effects. Thefts and murders were reduced almost to zero. Snarling animals became men. Tho just released from irons, they put themselves under the iron discipline of the Soviet armies. Lawless under the old law, they became the writers and defenders of a new law. Men who had so many wrongs of their own to brood over now assumed the wrongs of the world. They had vast programs to release their energies upon, vast visions to light their minds.

To the rich and the privileged, to those who sit on roof-gardens or ride in parlor-cars, the Revolution is a thing of terror and horror. It is the Anti-Christ. But to the despised and disinherited, the Revolution is like the Messiah coming to "preach good tidings to the poor; to proclaim release of the captives and to set at liberty them that are bruised." No longer can Dostoyevsky's convict mutter, "We are not alive, though we are living. We are not in our graves, though we are dead." In the House of the Dead, Revolution is Resurrection.

Source: From chapter 14 of Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution. (Boni and Liveright, 1921), pages 207-217.