On the left sat the Bolsheviks

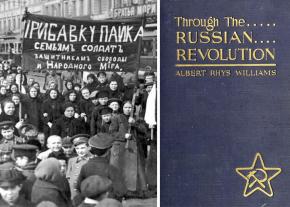

SocialistWorker.org is continuing its ongoing series 1917: The View from the Streets with a series of excerpts from a firsthand account of the revolution by socialist journalist and his book Through the Russian Revolution, published in 1921. Writing for the New York Evening Post, Along with the more famous Ten Days That Shook the World by fellow journalist John Reed, Through the Russian Revolution provides a riveting picture of the struggle to create a new society as Russian workers, soldiers, sailors and peasants began seizing control over every aspect of their daily lives.

In the excerpt below from chapter one, selected by Paul D'Amato, Williams talks about his contrasting introduction to the Bolsheviks--the slanders of the bourgeoisie on the one hand given lie by a visit to the home of a revolutionary in Petrograd. The excerpt is preceded by an introduction to Williams and his book written by Eric Blanc. SW's series on 1917 is edited by John Riddell and co-published at his website.

Introduction to Through the Russian Revolution by Eric Blanc

THROUGH THE Russian Revolution is a firsthand account by American socialist journalist Albert Rhys Williams of the mass upsurge that culminated in the Bolshevik-led seizure of power in Petrograd in late 1917 and the efforts to build a new social order in early 1918. Williams was an American socialist writer who went to Petrograd in the summer of 1917 to report on the Russian Revolution for The New York Evening Post. Though based in the capital, he also traveled extensively across the empire to observe the revolutionary process in the villages, among sailors in the Baltic, and on the military front.

Together with John Reed and Louise Bryant, Williams witnessed firsthand the October Revolution and the seizure of the Winter Palace. Williams became an active supporter of the Communists (though he never joined the party either in the Soviet Union or the U.S.). In 1918, under the coordination of Leon Trotsky, he edited German-language revolutionary publications aimed at German troops. Williams returned to the U.S. later that year in order to lead a major political-educational campaign against U.S. military intervention in Russia. In subsequent years, he wrote multiple pro-Soviet works.

The importance of Williams' account lies in its accessibility, its "bottom-up" approach, and its vivid depictions--few works give a reader a better feel of the revolution, while simultaneously and succinctly explaining the basic political debates of the period.

Williams' contributions made a major impact during the postwar radicalization in the United States–one New York Times editor claimed that "the greatest creation of Bolshevism is not Trotsky's army, but Albert Rhys Williams." But in the ensuing years Through the Russian Revolution has become not only out of print, but virtually forgotten in the U.S., perhaps because it was overshadowed by John Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World. Williams' book is less dense and covers a broader period of time than Reed's more famous work, and as such, it is generally more approachable for general readers. Significantly, unlike Reed's document, Through the Russian Revolution also describes the fascinating early efforts to build a new workers' state and put industry under workers' control

Through the Russian Revolution is a lost classic that should find a wide audience among those interested in learning about the Russian Revolution during and following the 2017 centennial commemorations.

Enter the Bolsheviks

This First Congress of Soviets was dominated by the intelligentsia--doctors, engineers, journalists. They belonged to political parties known as Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary. At the extreme left sat 107 delegates of a decided proletarian cast--plain soldiers and workingmen. They were aggressive, united and spoke with great earnestness. They were often laughed and hooted down--always voted down.

"Those are the Bolsheviks," my bourgeois guide informed me, venomously. "Mostly fools, fanatics and German agents." That was all. And no more than that could one learn in hotel lobbies, salons, or diplomatic circles.

Happily, I went elsewhere for information. I went into the factory districts. In Nijni I met Sartov, a mechanic who invited me to his home. A long rifle stood in the corner of the main room.

"Every workingman has a gun now," Sartov explained. "Once we used it to fight for the Czar--now we fight for ourselves."

In another corner hung an icon of Saint Nicholas, a tiny flame burning before it.

"My wife is still religious," Sartov apologized. "She believes in the Saint--thinks he will fetch me safely through the Revolution. As though a saint would help a Bolshevik!" he laughed. "Yeh! Bogu! There's no harm in it. Saints are queer devils. No telling what one of them may do."

The family slept on the floor, insisting that I take the bed, because I was an American. In this room I found another American. In the soft gleam of the icon light his face looked down at me from the wall, the great, homely, rugged face of Abraham Lincoln. From that pioneer's hut in the woods of Illinois he had made his way to this workingman's hut here upon the Volga. Across half a century, and half a world, the fire in Lincoln's heart had leaped to touch the heart of a Russian workman groping for the light.

As his wife paid her devotion to Saint Nicholas, the Great Wonder Worker, so he paid his devotion to Lincoln, the Great Emancipator. He had given Lincoln's picture the place of honor in his home. And then he had done a startling thing. On the lapel of Lincoln's coat he had fixed a button, a large red button bearing on it the word: B-o-l-s-h-e-v-i-k.

Of Lincoln's life Sartov knew little. He knew only that he strove against injustice, freed the slaves, that he was reviled and persecuted. To Sartov, that was the earnest of his kinship with the Bolsheviks. As an act of highest tribute he had decorated Lincoln with this emblem of red.

I found that factories and boulevards were different worlds. A world of difference, too, in the way they said the word "Bolshevik." Spoken on the boulevards with a sneer and a curse, on the lips of the workers it was becoming a term of praise and honor.

The Bolsheviks did not mind the bourgeoisie. They were busy expounding their program to the workers. This program I got first hand from delegates coming up to the Soviet Congress from the Russian Army in France.

"Our demand is, not to continue the war, but to continue the Revolution," these Bolsheviks blurted out.

"Why are you talking about revolution?" I asked, taking the role of Devil's advocate. "You have had your Revolution, haven't you? The Czar and his crowd are gone. That was what you were aiming at for the last hundred years, wasn't it?"

"Yes," they replied. "The Czar is gone, but the Revolution is just begun. The overthrow of the Czar is only an incident. The workers didn't take the government out of the hands of one ruling class, the monarchists, in order to put it into the hands of another ruling class, the bourgeoisie. No matter what name you give it, slavery is the same."

I said the world at large held that Russia's task now was to create a republic, like France or America; to establish in Russia the institutions of the West.

"But that is precisely what we don't want to do," they responded. "We don't cherish much admiration for your institutions or governments. We know that you have poverty, unemployment and oppression. Slums on one hand, palaces on the other. On the one side, capitalists fighting workmen with lockouts, blacklists, lying press, and thugs. Workmen on the other side, fighting back with strikes, boycotts, bombs. We want to put an end to this war of the classes. We want to put an end to poverty. Only the workers can do this, only a communistic system. That is what we are going to have in Russia."

"In other words," I said, "you want to escape the laws of evolution. By some magic you expect suddenly to transfer Russia from a backward agricultural state into a highly organized cooperative commonwealth. You are going to jump out of the 18th century into the 22nd."

"We are going to have a new social order," they replied, "but we don't depend on jumping or magic. We depend upon the massed power of the workmen and peasants."

"But where are the brains to do this?" I interrupted. "Think of the colossal ignorance of the masses."

"Brains!" they exclaimed hotly. "Do you think we bow down before the brains of our 'betters'? What could be more brainless and stupid and criminal than this war? And who are guilty of it? Not the working classes, but the governing classes in every country. Surely the ignorance and inexperience of workmen and peasants could not make a worse mess than generals and statesmen with all their brains and culture. We believe in the masses. We believe in their creative force. And we must make the Social Revolution anyhow."

"And why?" I asked.

"Because it is the next step in the evolution of the race. Once we had slavery. It gave way to feudalism. That in turn gave way to capitalism. Now capitalism must leave the stage. It has served its purpose. It has made possible large-scale production, worldwide industrialism. But now it must make its exit. It is the breeder of imperialism and war, the strangler of labor, the destroyer of civilization. It must in its turn give place to the next phase--the system of Communism. It is the historic mission of the working-class to usher in this new social order. Though Russia is a primitive backward land it is for us to begin the Social Revolution. It is for the working class of other countries to carry it on."

A daring program--to build the world anew.

Source: From chapter one of Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution. (Boni and Liveright, 1921), pages 14-19.