Chavismo after the election

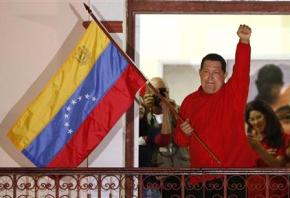

Venezuela's left-wing leader Hugo Chávez, after handily winning reelection to a fourth term as president in October, has been politically sidelined by the recurrence of cancer, for which he went to Cuba for surgery and treatment in December. He hasn't been seen in public since, though family members said this week that he would return to Venezuela soon.

Chávez was supposed to be sworn in earlier this month, but the National Assembly agreed to postpone the inauguration. For now, Vice President Nicolas Maduro presides as chief of state, but much depends on whether Chávez returns, and his condition if and when he does. This has raised profound questions about the future of Venezuela and the radical government the former military officer-turned-left wing political leader has headed since 1999.

As background to the debates now taking place in Venezuela, we publish this roundtable with members of the radical left Marea Socialista (Socialist Tide) current within the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) led by Chávez. The interview took place in October, after Chávez's victory. Participants included Gonzalo Gómez, founder of the website Aporrea.org; Stalin Perez Borges, a trade union leader; Juan García; and Zuleika Matamoros. The roundtable was conducted by for Europe Solidaire Sans Frontieres--an English translation appeared at the VenezuelaAnalysis.com website.

IN YOUR opinion, what importance does the election victory of Hugo Chávez have? What are the main points and what will its regional impact be on Latin America?

Gonzalo: Firstly, in the light of the election results, it should be noted that Chávez has won, and with him, it is the people who won. The Chávez re-election means that the revolutionary process remains open in Venezuela and extends the opportunity for further progress of the social and political transformations that have marked the Bolivarian revolution.

Juan: The October 7 election prevented the bourgeoisie and imperialism from halting the Bolivarian revolution. The country continues to pursue an orientation of relative independence in relation to imperialist domination. The bourgeoisie has not managed to gain the space that would allow it to restore its neoliberal policies and its direct control of the state, of which it was deprived by the revolutionary process.

Gonzalo: With regard to the regional impact, the victory of Chávez and the relationship of forces in Latin America continue to be favorable to the revolution and to so-called "regional integration." The interventionist, imperialist option was weakened and delayed, which paves the way for other strategies that they may attempt to use to neutralize the Bolivarian revolution on the Latin American geopolitical scene.

Zuleika: Having said that, even if we begin our analysis by recognizing the significance of the triumph of Chávez, we must also recognize the growing threat of the right. In this election, the margin in favor of Chávez was slightly more than 11 percent of the votes, which is very significant. But we must not forget that, compared to previous elections, such as the 2006 presidential election, Chavismo has diminished its lead among voters, and the right has made advances.

Juan: Zuleika is correct, and we must draw attention to this in the discussion that will follow the elections. In 2006, Chávez won almost 63 percent of the vote while the candidate of the right won nearly 37 percent. The margin in favor of Chávez was 27 percent. In the October 7 election, Chávez won with slightly more than 55 percent while Henrique Capriles Radonski got slightly more than 44 percent; the gap has been reduced to less than 12 percent.

In terms of the absolute number of votes, Chávez received around 800,000 more votes than in 2006, while the right won 2.1 million more votes, which means there were around 3 million new voters (based on approximate figures available at the time of the interview). Chávez won in 22 of the 24 states, and the right lost the majority in many regions that it led. But it has also been strengthened in many big cities and has advanced significantly, both in percentage terms and in its absolute number of votes.

Stalin: This is why you need to draw attention to the danger posed by this trend. If electoral patterns continue to evolve in the same way that we observed on October 7, there is a serious danger that the next Bolivarian presidential nominee (Chávez or anyone replacing him) would lose the presidency, and the right would have a great chance of winning. This risk may occur even before Chávez's new term is up, if the bourgeois opposition is able to call a presidential recall referendum, as it did in 2004.

That is why, although we celebrate this victory, we also say that there is a problem because Chávez has gone backwards, while the right has gone forward. And this has happened at a time of the highest voter turnout in any recent national election. So we can speak of electoral erosion for Chávez.

BEFORE WE talk about the reasons for this erosion, can you talk a bit about the program of the candidate of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) during this campaign?

Gonzalo: Chávez presented a program grounded in five historical objectives. His campaign sought to make an emotional attachment, an emotional bond with the people. To do this, he used the slogan, "Chávez, the heart of the country." But this slogan, beyond the psychological impact it had, was by no means an ideological principle of the left and could be used by his opponent to the right, Capriles Radonski.

Of course, Capriles Radonski doesn't have the emotional appeal of Chávez among the population, and his image is not associated with feelings of patriotism, sovereignty and national independence that Chávez wanted to connect with.

But in reality, the objectives set out in the programmatic proposals of Chávez were little discussed, and his campaign was more focused, especially in the final weeks, on a denunciation of the threats posed by the neoliberal agenda of Capriles and his rightwing Coalition of Democratic Unity (MUD) to the national independence won during the 14 years of the Bolivarian revolution.

Juan: This country has been marked, historically, by the 1989 rebellion against attempts to impose a package of neoliberal measures designed by the International Monetary Fund. It was the revolt of February 27, 1989, that initiated the revolutionary period that we are still living through, and that is how the figure of Chávez--as well as the constituent process that took place after he came to power in 1998--emerged.

That is why the denunciation of Capriles' intentions to challenge these policies has had a great impact. Here, the "specter of communism" that the right always uses to scare people into believing that they will lose their personal property has backfired. This time, it's Capriles who has embodied the threat that the Venezuelan people would lose the gains accumulated under the mandate of Chávez: access to health care, education, housing, pensions, the reduction of poverty and so on.

Zuleika: With regard to the people's movement, it was stifled by the PSUV and the machinery of government. The Great Patriotic Pole, which had generated great expectations and was seen as an opportunity to create an enthusiastic campaign, which was to be a space of participation for the rank and file and other social forces, was deflated because its policy initiatives were sequestered by the PSUV and the electoral machine, which imposed their line.

It is distressing because during the elections of 2006 the participation of the rank and file was much more vigorous and produced better results. This election campaign was much more bureaucratically controlled, and it became a source of political damage. The PSUV was not up to it, it was not the true engine of the campaign because of the insistence of the bureaucracy on stifling the initiatives of the rank and file and the autonomy of the social movements.

Ultimately, the most important factor in this campaign was Chávez himself, who really threw himself into it during the last weeks, as well as the participation of the population, which was aware of the threat posed by the right. The people were engaged despite the fact that their enthusiasm has been undermined by previous bad experiences of the bureaucratization of the process.

HOW DO we analyze the Capriles campaign, his achievements in the construction of a united opposition for the presidential elections, his actual ability to mobilize the masses well beyond the "hard core" of the right (and the oligarchy), and his electoral results in Caracas and in the provinces?

Stalin: With the help of imperialism and on its orders, the right managed to unite throughout a major election, regardless of its internal tensions and its minor fractures.

From the point of view of its own objectives, it has waged a very successful campaign and has been able to reach disgruntled popular sectors, who, despite the benefits obtained, resent the abuse of the governmental bureaucracy within public institutions and state enterprises, just as they resent its lack of consistency and its ineffectiveness with regard to the issues which cannot be resolved in the context of capitalism.

For the first time in years--in fact, since the failed coup of 2002--the right was able to mobilize in the center and west of Caracas, in Chavista and popular areas, and gather some 150,000 people in the capital on Bolivar Avenue. But the Chavista popular reaction on October 4 mobilized five or six times more people at the same time to adjacent areas.

That said, it is clear that the right has been able to penetrate little by little into the popular sectors, in particular the so-called "middle class," who feel dissatisfied and hold Chávez responsible for unsolved problems, such as insecurity and delinquency.

AFTER THIS victory, a new period of six years of government opens, which will be the last government of Hugo Chávez. How is he going to address important issues, such as bureaucracy, clientelism, state inefficiency and insecurity?

Gonzalo: If we analyze the trend of electoral growth for the right and take into account the uncertainty generated by the possibility that the right will not have to confront Chávez in the next election, we cannot rule out the possibility that what happened to the Sandinistas at the end of the 1980s, when the bourgeoisie returned to power, could happen here.

If we do not advance anti-capitalist measures and if the bureaucratization continues, if we do not build a collective, popular and working-class leadership of the revolutionary process, if the extreme dependence on Chávez continues...the erosion may be irreversible. That is why Marea Socialista says we need to push for--with all our strength--the exercise of social control and genuine participatory democracy against bureaucratism.

We think it is necessary that Chávez opens permanent consultation with the organizations of the working class, the peasants, organs of popular power and social movements active in the process, so as to share in the design and approval of policies. We need a revival of constituent input around the new program presented by Chávez in this election as well as a renewal of the participation of social actors in the exercise of governance of a revolutionary type. It is with these movements that we need to identify the priorities and the measures to be implemented.

THE PRESIDENT has been weakened by his illness, and yet he was very active in the last weeks of the campaign, and there is no doubt that his popular and charismatic leadership was fundamental to the victory. Is a "Chavismo without Chávez" imaginable?

Juan: Without Chávez as a factor and without the construction of a collective leadership originating from the organized people, we believe that "Chavismo" will sink into dissolution and confusion. That is why we are saying we need to build a new government that would be the real expression of the popular movement and organizations of the working class.

WHAT ARE the medium- and long-term perspectives of the Bolivarian process? And what are some of the debates within the political space of Bolivarianism regarding the deepening--or not--of its victories and regarding how to transcend its contradictions? And what stance does your current, Marea Socialista, take in this debate?

Gonzalo: We increasingly insist on the need for a radical left current in the revolutionary process. While the government spoke recently of the need for a "responsible right" with which it is possible to have a dialogue, we--and a good part of the radical activists--believe that what is needed is a consistent revolutionary left able to push for a change of direction.

It must be a force able to guide the implementation of the policies that will complete the break with capitalism, to allow us to go beyond the "mixed economy" schema and facilitate the transition to socialism. The construction of the new society has been slowed by bureaucracy, thus delaying the solution of problems both urgent and structural.

WHERE ARE we in relation to the experiences of popular participation, such as experiences in workers' control (at Sidor, for example) and popular power at the neighborhood level (communal councils) and the communes? We hear much about 21st-century socialism, but the campaign has focused on more "emotional" or general slogans, such as "Chávez, the heart of the homeland." What does "21st-century socialism" mean beyond the rhetoric?

Stalin: As you have noted, the rhetoric often takes precedence over concrete policy. In the case of workers' control, we recognize that Chávez has created the potential to experiment with it on the basis of the fight that the workers led, but the behavior of the state bureaucracy stifles and distorts these experiences.

The task that we face is to overcome these challenges by increasing our capacity to fight and deepening revolutionary consciousness. As for popular power, the neighborhood councils and communes have been a very progressive experience, but they remain confined to the local level, and these emerging organizations must also contend with bureaucratization and cooption by the state and clientelist relations. There is no specific policy that would allow them to expand from the neighborhood level to a real involvement in the exercise of territorial and national power.

That is why we say that Chávez should make a call--and we must demand it--so that the structures of popular power, as well as the social movements, that we have built have a right to expression at the level of the government and over the policies the government implements. We need a clearly anti-capitalist and socialist orientation, and that means the real implementation of the power of the workers and the people.

This English translation appeared at the VenezuelaAnalysis.com.