Honoring a victim of the Oakland police

By

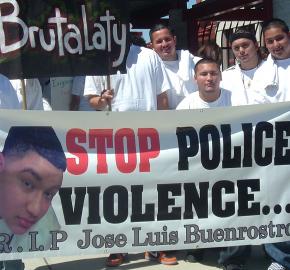

OAKLAND, Calif.--Chanting "What do we want? Justice! When do we want it? Now!" more than 100 students, teachers, family members and community activists, clad in white and carrying banners and homemade signs, marched May 17 in honor of José Luis Buenrostro-Gonzalez, a 15-year-old boy shot dead by three undercover Oakland police on March 19.

The march began with a rally at Acorn Woodland Elementary school on 81st Avenue in East Oakland, near José Luis' home, and ended at the Eastmont Mall police station.

"We are marching to demand justice, to stop police violence against the youth," María Buenrostro, José Luis' mother, said. "I hope other parents come out to support us, because this hit me this time, but next time, it could be you."

Nearly two months after the incident, police still refuse to even release the names of the officers involved and have continued to repeat the unsubstantiated charge that José Luis and his family were "linked" to gang activity.

But despite attempts by police to smear the family, the Buenrostros, led by older sister Maggie Buenrostro, have received significant support from community groups like ACORN, and many educators, including the president of the Oakland Education Association (OEA) teachers' union, Betty Olsen-Jones.

"I have just had a very moving and sad conversation with José Luis' mother," said Olsen-Jones, as she addressed the May 17 rally. "You know, here in California we are 47th in the nation in school spending, but number one in prison spending, and kids like José Luis end up losing. We've got to organize to change this. The OEA is here to help."

In addition to demanding justice for José Luis, teachers are upset that the police are ignoring the safety of their students.

"It was very scary," explained third grade teacher Ratha Chan. "We heard the shots, but the police didn't even come to tell us what had happened.

"One of the things we want is for the police to contact a school 10 minutes before they do anything that might be dangerous. I have a friend who works at Webster Elementary, just down the street on 81st Avenue, where the cops are constantly raiding this one house with SWAT teams at 8:30 in the morning, when the kids are outside lining up for school, or at 3:30 in the afternoon, when the kids are going home. And they don't even know if there are going to be shots fired or stray bullets."

UNEMPLOYMENT IS rising quickly in Oakland because of the recession, and the murder rate is increasing right alongside it. So far this year, there have been 53 murders, up from 37 at this time last year--a pace that will once again make Oakland (with a population of around 400,000) one of the three or four most violent cities in the country.

This has led to an outcry from politicians for more police on the streets. However, not only are they ineffective in stopping the violence, the Oakland police have a grim record of contributing to it.

Earlier this month, the city of Oakland paid $100,000 to settle a civil lawsuit brought by Ameir Rollins, who was shot in the neck by Officer Pat Gonzalez and left a quadriplegic on June 5, 2006, when he was just 17 years old. Although the police denied any wrongdoing, Gonzalez had already shot and killed two other people in the four years before shooting Rollins--Joshua Russell, age 19, and Gary King, Jr., age 20. Not only has the city steadfastly defended Gonzalez, they have promoted him to sergeant.

While the city rushes to hire dozens of new officers who will be trained by the likes of Gonzalez, some teachers worry about the impact of police violence on students.

"I was teaching that day," said Ashley Martin, a fifth grade teacher. "Half of my kids were at recess when one of my students came up to me and said that his friend just got shot. All of our kids were out here at 12:30 p.m. The police didn't even notify the school that something was going to happen.

"It was completely unsafe for our kids. They shot him just over there, and our kids were right here on the basketball court, just a few hundred yards away. We had counselors come in and talk to the kids for two days. A lot of the kids knew his younger sister, who was a student of ours."

Mayor Ron Dellums' staff had agreed to meet with the Buenrostro family on May 15, but refused to set a specific time, allowing the meeting to fall through. It seems as though Oakland police and politicians are counting on José Luis' memory fading quietly away.

But his family and friends are determined not to let that happen. Even as they continue to press the city to release the names of the officers, they are taking their own actions. "We want to create a permanent public memorial for José Luis," said his mother María. "And we want the police to promise that they will respect it."