Their heads held high

celebrates the life of Los Angeles educator and activist Sal Castro.

SAL CASTRO, the inspirational teacher-activist who encouraged Chicano students to take a stand against educational inequity in the 1968 high school "blowouts," died April 15 at the age of 79 after a bout with cancer.

Salvador Castro was born in Boyle Heights on the East side of Los Angeles to Mexican immigrant parents in 1933. He was attending kindergarten in East LA when his family was forced to move to Mexico during the unconstitutional "Repatriation Movement," in which as many as half a million people of Mexican descent were forced out of the U.S.

In Sinaloa, Mexico, Sal learned to read in Spanish. When he returned to the U.S. for second grade, his teacher made him sit in a corner because he was the only student who couldn't speak English.

Even at this young age he knew something was wrong. "I started thinking, these teachers...should be able to understand me," he later told the Los Angeles Times. "I didn't think I was dumb--I thought they were dumb."

Sal graduated from high school and was drafted into the Army toward the end of the Korean War. He attended LA City College and Cal State LA on the G.I. Bill, and got his teaching credential. He held several teaching positions before being hired at Belmont High School near downtown LA.

There, Castro saw that the unjust conditions he had experienced in LA schools continued to prevail. Students were punished for speaking Spanish, corporal punishment was still allowed, campuses were rundown, and Mexican American students were routinely tracked into vocational rather than college prep classes. "It was like American education forgot the Latino kid," he told the Times.

AT BELMONT High School, Castro encouraged Mexican American students to run for student government. When some of the students he coached gave their campaign speeches in Spanish, the students were suspended and Castro transferred from Belmont to Lincoln High School in East LA

Castro joined the Association of Mexican American Educators, a group of graduate students who made recommendations to the LA County Board of Supervisors on how to improve education for Mexican Americans. The only recommendation the board acted on was the creation of an "urban affairs liaison" which did nothing to address inequality.

In 1963, Castro helped found the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference (CYLC), which became a training ground for student activists and continued until 2009.

At CYLC conferences, students discussed inequalities between schools within the LA Unified School District, the need for bilingual and culturally relevant education, and the need for systemic reforms that would place students on the track to higher education. They founded the Piranya Café, which became the headquarters for the movement.

At Lincoln High, Castro worked with students and recent graduates to come up with a list of demands to improve school conditions and educational opportunities. When the school board ignored their demands, talk of a school boycott began to circulate.

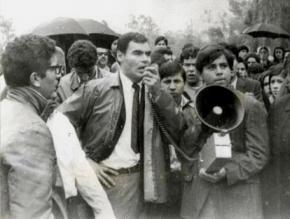

On March 1, 1968, 300 students walked out of Wilson High School after the school play was canceled due to its "risqué" content. The next day, another walkout was staged to protest a school policy against male students wearing long hair. After these small walkouts, student activists met to coordinate demands for unified protests, and by the end of the next week, 15,000 students had walked out of five East LA high schools.

In the documentary Chicano! Castro describes the day of the walkouts at Lincoln:

In the morning...as the bell rang for the kids to go to school, heading for their classroom--out they went. Kids from all over, different hallways and everything else, they were out in the streets with their heads held high, with dignity. It was beautiful to be a Chicano that day.

The "Chicano blowouts" brought Chicanos into the national consciousness as part of the youth radicalization of the 1960s. It also brought the movement to the attention of authorities, who responded with brutal repression.

Police viciously attacked students at Roosevelt and Belmont High Schools, and 13 activists, including Sal Castro, were indicted by the LA County Grand Jury on 30 counts of conspiracy for their roles in organizing the strike.

Castro was jailed for five days and lost his job, but was reinstated after weeks of protest by Eastside parents. After being bounced around to different schools, Castro landed back at Belmont in 1973, where he taught and counseled thousands of students until his retirement in 2004.

Castro was a strong union supporter, who attended rallies and continued to speak out for educational justice even after his retirement.

Sal Castro was the kind of social justice educator many of us aspire to be today. He took a stand for his students, but more importantly, he helped his students take a stand for themselves. As Carlos Muñoz noted in Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement:

Castro came to the conclusion that his people needed their own civil rights movement and that the only alternative in the face of a racist educational system was nonviolent protest against the schools. He therefore prepared to sacrifice his teaching career, if necessary, in the interest of educational change for Mexican American children.